The concept of remote work is not novel. In theory, certain jobs can be easily done outside the traditional office. Still, models of remote work vary across the globe, just as a teacher in Germany might have a dissimilar experience than one in Argentina or Taiwan.

After the December 2019 Sars-CoV-2 outbreak, which quickly spread into a pandemic, work & project management have been implemented for work-from-home environments (WFH, for short). In light of COVID-19, project management software and online video conferences have been the nut and bolt of the remote work environment. Last year, 2021, gave us an overview of the remote work status worldwide.

The world at large

So, who can actually work remotely? Before we jump right into some remote work statistics, we have to address a few dimensions to understand why remote practices vary across regions. Pardon the broad generalization as we talk about high, mid, and low-income countries.

Any developed capitalist economy is characterized by a dual labor market divided into primary and secondary sectors. Simply put, the primary market features highly-paid, well-educated, white-collar employees, while the secondary market involves low-paying, low-skill, blue-collar workers (or low-prestige jobs).

The primary market attracts mostly natives who benefit from job security, perks, and career advancement prospects in safe working conditions. The secondary market leaves room for migrant workers, who might encounter fewer opportunities for promotion, low-to-minimum wages in poor working conditions, and job insecurity.

We won’t delve into the economic and socio-political factors that influence this dualism, but what’s certain is that COVID-19 destabilized economies all around the world.

The WFH potential. Who can work remotely?

So, within the framework of a dual economy, let’s discuss the potential of working from home. We’ll call it ‘WFH potential’ for short. It has three dimensions: ‘telecommutability’ (the ability to be adapted to remote environments), technological infrastructure (e.g., Internet access), and geographic variation.

Dingel & Neiman (2020) employed the Occupational Information Network (called the O*NET) to find which jobs are ‘telecommutable,’ that is, which jobs can be performed outside the traditional workspace. For instance, an IT developer, a government worker, and a plumber can work from home to a certain extent.

In light of the pandemic, an IT developer can work fully remote and experience no change in work practices, and a government worker may need to adopt a hybrid model. In contrast, a plumber might need to change the work style altogether (e.g., to offer consultancy or help over the phone/video call to interested DIYers).

So, in hindsight, what the COVID-19 pandemic has engendered is a stronger polarization of the two markets since jobs from the primary sectors can be done from home.

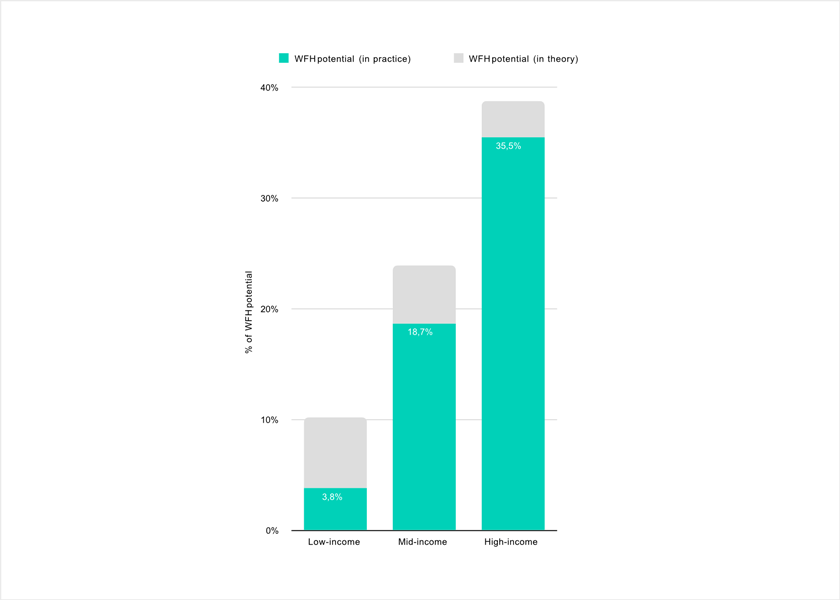

Let’s outline some statistics about the WFH potential on a global scale (provided by the World Bank, 2020):

1. The WFH potential in low-income countries has an average of 10.2% (in theory), which drops to 3.8% (in practice).

For example, the WFH potential for Nepal would be 14.7% but drops to an actual 6.3%. The WFH potential in Ethiopia is 5.5% but is reduced to half, to just 2.1%.

2. The WFH potential in mid-income countries averages 23.9% (in theory), dropping to 18.7% (in practice).

Take India, for instance; there’s disparity among the mix of sectors. Knowledge workers have higher chances of working remotely due to the nature of their jobs (writers, accountants, designers, architects, etc.). An employee from the top earnings percentile has a 19% chance of switching to remote work, but an employee from the bottom percentile has less than a 1% chance for WFH.

3. High-income countries have a WFH potential average of 38.8% (in theory) which drops to 35.5% (in practice).

Internet access is barely an issue in developed European countries like Switzerland, Sweden, the UK, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. So, the WFH potential ranges between 40 to 55%.

The WFH potential shows us that, realistically speaking, even if the world at large tried to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, there’s a cap on how much can be done working from home (at least in the current state of events).

The findings are unsurprising. Developed countries with a potent primary market are implicitly high-income, which in turn have a higher WFH potential. In comparison, low-income countries have fewer jobs that can be done from home. Plus, this rate drops considerably if you factor in Internet penetration and speed.

Figure 1. The WFH potential disparity among low, mid, and high-income countries.

Geographic variation

Even among rich countries, there’s geographic variation when it comes to WFH potential:

4. Metropolitan areas are more likely to be amenable to home-based work than rural areas.

The contrast is starker in European countries like Spain, France, Portugal, Romania, and Poland.

There’s a North-South divide in Mexico and a mainland-coastal divide in the United States and Brazil, where the wealthier areas are closer to the coast. Turkey has an NW-SE divide, with remote work arrangements in metropolitan areas like Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir.

Even though there is a wealth divide among states in India– with more prosperous areas down south– interestingly, there is little variability in remote work because of poor Internet connection throughout the country. Plus, although India is known for its knowledge economy, its vast majority is employed in retail and agriculture, which cannot be done remotely (McKinsey, 2021).

Internet access

Besides geographic variation, the problem with remote work is that most jobs that can be done remotely require technological infrastructure, namely Internet penetration and good connection.

5. There are 4.66 billion active Internet users as of January 2021 (Statista, 2021).

In other words, only 59.5% of the global population has access to the Internet in 2021.

Although China (1.44 billion) and India (1.39 billion) lead the top when it comes to the number of active users – followed by the United States (332 million) – China (65.2%) and India (45%) have a lower Internet penetration rate than in the United States (90%) and Europe (average of 91%). The United Arab Emirates has the highest Internet penetration rate at 99%.

Besides Internet access, a steady connection is necessary for good remote work:

6. The global average download speed on fixed broadband is 107.50 Mbps in July 2021. (Speedtest® by Ookla®, 2021)

This shows that lagging Zoom meetings and frequent disconnections are a reality in countries with slow Internet, e.g., India (60.06 Mbps). Especially if you compare it to Singapore (256.03 Mbps), Hong Kong (248.59 Mbps), Romania (215.30 Mbps), Switzerland (214.82 Mbps), South Korea (212.83 Mbps), Chile (209.45 Mbps), and Denmark (208.50 Mbps), to name a few. So, even if jobs can be done remotely, frustration still can bubble up. Even in the United States,

7. Only 65% of remote workers have Internet fast enough to support video calls (Stanford News, 2020).

Besides poor Internet, Stanford economist Michael Bloom argues in a policy brief for SIEPR (2020) that working conditions from home are not optimal for most Americans:

8. Only 49% of American employees work from a dedicated room. Plus, the other 35% have such poor Internet at home (or none at all) that it prevents any WFH arrangement.

Thus, 51% work from shared spaces. In a survey by Owl Labs (2020), 67% of respondents mentioned working from their home office, 49% from their dining room, 49% from their couch, 42% from their bedroom, and 15% from their closet.

We won’t delve into more details. To understand the impact workspace has on remote work, we recommend you read this compelling article on How your space shapes how you view remote work.

The key takeaway of this section is that telecommutable jobs are unequally distributed across space, including within countries. Surely, COVID-19 affected poorer countries and households more negatively than the more prosperous ones. So, governments unwilling or incapable of adopting home-based work policies will only widen this gap in GDP. Simply put, remote work is not only necessary; it generates wealth.

Remote work statistics pre & mid COVID-19 (2019 & 2020)

Before the pandemic in 2019, it was estimated that

9. Only 7.9% of the global workforce adopted remote work practices (Eurostat, 2019; Statista, 2019; ILO, 2019).

The total global workforce was estimated at 3.3 billion in 2019. Let’s take a look at a few high-income countries for a quick breakdown:

- 12% in the United States — out of 157.54 million

- 10.8% in Europe — out of 183 million

- 4.8% in Japan — out of 68.86 million

- 4.7% in South Korea — out of 28.54 million

- 2% in Australia — out of 12.92 million

In Europe, Sweden leads the top (31.3%), followed by Switzerland (27.7%), Iceland (24.1%), the Netherlands (23%), and the United Kingdom (21.7%).

10. Italy is a straggler – its remote work rate was 1% in 2019.

This means that of the total workforce of 23.36 million, only 233,600 employees had any WFH arrangement. Italy is only followed by Romania and Bulgaria (both 0.6%) when adopting remote work nationally. Still, these two represent emerging markets, and it’s argued they have room to grow.

As expected, due to the outbreak of Sars-CoV-2,

11. Remote work has experienced a sharp rise beginning in March 2020:

- 42% in the United States

- 40% on average in Europe

- 32% in Australia

- 24.9% in South Korea

- 10% in Japan

Due to strict coronavirus regulations, the United States peaked at 61% in the remote workforce in the summer of 2020 and stabilized to 42% soon after.

Similarly, Italy also peaked at a whopping 61% (from 1% no less!). This is because Italy had been the gateway and primary hotspot of COVID-19 infections in February 2020, so it has made painstaking efforts to stabilize the country.

As for the rest of Europe, Finland maintained an average of 60% (from 17.7% in 2019) throughout 2020. Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, and the UK rank within the 5th decile. Ireland, Austria, Sweden, and Italy maintain an average remote workforce within the 4th decile.

Australia closed its borders in 2020 and enforced strict quarantine measures, maintaining a 32% remote workforce.

12. So, in addition to the already-employed remote workers, over a third of American, Australian, and European employees started working from home due to the pandemic (Eurofound, 2020).

These 2020 statistics prove that the WFH potential falls between normal ranges estimated for developed countries, namely close to 40% (as discussed in the previous section). In addition, the McKinsey Global Institute corroborates that the average WFH potential is 39% when averaging all economic sectors.

Studies show that WFH arrangements are directly proportional to the level of economic development. Countries that rely primarily on manufacturing, agriculture, construction, and tourism make teleworking difficult because they require in-person work and face-to-face activity.

Conversely, high-income countries feature more jobs from the primary labor market in information and communication technology (ICT), finance, and public administration.

According to a study conducted by McKinsey Global Institute on 800 jobs in the United States,

13. Finance and insurance (76%), followed by management (68%), and professional services (62%), are the top 3 sectors comprising jobs that can be done remotely without losing effectiveness.

On the opposite pole, agriculture (7%), hospitality (8%), and construction (15%) are the bottom three sectors in terms of WFH potential.

What’s more, with proper adjustments to WFH practices, there’s a theoretical maximum of 86% for finance and insurance, 78% for management, and 75% for professional services. Yet, there’s only 8% for agriculture, 9% for hospitality, and 20% for construction.

The statistic is not baffling. It’s pretty evident that such jobs can be easily applied to WFH in high-income countries. There’s one exception, though, and it bewildered its peers— Japan:

14. Japan has the lowest WFH rate (10%) among developed high-income countries (Okubo, 2020).

What’s up with Japan? Why is there a +30% increase in the remote workforce in Europe and the United States but only +5.2% in Japan?

The first explanation is an unexpected one— heavy reliance on paper. Due to a lack of digitization, Japanese workers find it challenging to work from home. That’s why they must go to the office to process paper invoices and use their seal of authorship, their Hanko stamp, on their contracts and paperwork.

Surprisingly, most Japanese don’t own personal computers at home. The Japan Productivity Center (2019) found that the household penetration rate fell to 69% in 2019 and that only 1% of owners use VPNs. Overall there are poor physical environments suitable for remote work due to the lack of Wi-Fi and IT equipment.

For this reason, companies and employers are expected to supply equipment, such as laptops and routers, along with the necessary software to make remote work possible. Due to low budgets, there has been a low uptake of (online) tools, which left employees feeling disappointed with management.

15. Only 1 in 10 Japanese workers were able to work from home in 2020. (Dooley, 2020), which rose to 2 in 10 by June 2021.

Due to intense efforts to mitigate the effects of COVID-19, remote work practices spiked to 30% in May 2020 but dropped to around 20% and stagnated until June 2021.

This stagnation shows that the messaging of authorities was not reaching employees and employers alike. One year in, and most countries have built infrastructure for proper remote activities— we’ll talk about South Korea in a minute.

So, there must be another valid explanation for why Japanese employees resist remote work. And that explanation might be that Japanese work processes differ from Western societies (Kyodo, 2020).

Task management in Japan is more cohesive and interdependent. This means that project managers spend more time and effort dividing tasks and allocating human resources when tasks are not clearly assignable.

Also, constant on-site training by older staff is vital. This interdependency, this need for mentoring is probably based on the Confucian senpai-kōhai relationship (senior-junior relationship).

East Asian work culture favors building relationships with coworkers, stakeholders, customers, clients, etc. There’s a much greater emphasis on close communication, space-sharing, team dinners, and face-to-face communication.

Some Japanese employees pin their refusal to adjust to remote work on solidarity. They believe working from home is unfair when others cannot. Plus, if others can go to their office, they should too.

This phenomenon is called “presenteeism,” which might be rooted in collectivism and the idea of being in accord with others. Workers aren’t productive but, at the same time, don’t want their superiors to perceive them as slacking off.

Let’s take a look at another East Asian work culture, namely South Korea:

16. 1 in 4 South Koreans managed to work remotely starting in April 2020 (Cho et al., 2021).

Why is there such a stark contrast between Japan and South Korea regarding remote work? Both countries are similar in work culture (sunbae-hoobae relationship in Korean), and both use the personal seal of authorship (Ingam dojang in South Korea).

Although the work culture is similar to Japan’s, South Korea resorted to teleworking due to economic pressures generated by an intense market polarization.

South Korea’s primary labor market is characterized by large corporations, unionized workers, and regular positions. So, in case of an economic downturn, these employees are protected, unlike their counterparts from the secondary labor market – SMEs, non-unionized workers, and nonregular positions.

17. The remote work rate peaked at 37% in July 2020 and stayed at 25% for months. This is to show that South Korea adapted its WFH practices.

In addition, South Korea imposed stricter regulations and policies to help combat the spread of COVID-19 than Japan because South Korea feared a stronger recession and high unemployment rates.

Starting in April 2020, South Korea adopted new measures to create infrastructure to make jobs amenable to remote work. There were efforts to digitize work processes, create a remote work culture, and encourage employees that WFH was the best approach (Lee et al., 2021).

Which country would you say had the stricter measures? The answer is— China. This leads us to the following statistic:

18. China peaked at 75% in remote work in July 2020, the highest percentage worldwide. (NRI, 2021)

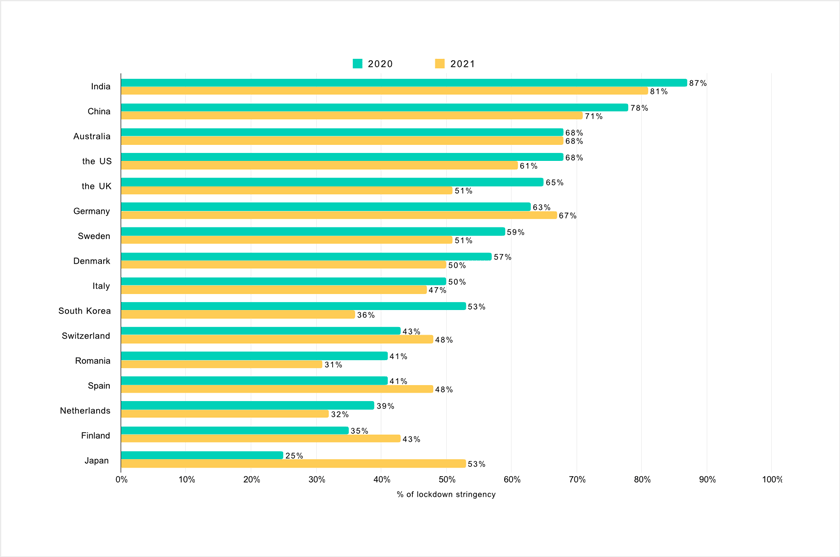

The high adoption rate of remote work was not influenced by belief in the model but due to lockdown stringency through restriction measures, penalties, travel bans, and closures of schools, places of worship, institutions, workplaces, etc. On the lockdown stringency scale calculated by Oxford University—interactive chart: OxCGRT—in July 2020 versus July 2021:

Figure 2. Data pulled from the OxCGRT on the first day of July of 2020 versus 2021, comparing the percentage of lockdown stringency.

The findings suggest that the countries with initial stricter policies (meaning over 50% in stringency) loosened their lockdown measures by July 2021 (except for Germany), while the two laxest countries (under 35%) tightened their policies, i.e., Finland and Japan.

The Japanese government had lenient lockdown policies – no lockdown nor penalties; the government kindly asked companies to reduce their operations and have their employees work remotely. Okubo et al. (2021) say this “soft approach based on self-restraint without penalties, punishments, regulations, or a lockdown” may explain the low uptake in WFH.

However, by 2021, the Japanese government had doubled its stringency in preparation for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games (July 23, 2021 – August 8, 2021). This stringency was coupled with efforts from a new government institution, “The Digital Agency,” to promote digitalization and teleworking.

Employee perception of remote work

In a study by the Nomura Research Institute (NRI), employees gave their subjective opinion on their remote work experience. When it comes to perceived productivity and flexibility in adapting to remote work practices,

19. East Asian countries like Japan, China, and South Korea perceived some loss in productivity (NRI, 2021).

According to Riskybrand (MINDVOICE®, 2020), employees showed concerns regarding remote work. Millennials (83%) and Gen Zs (89%) were initially the most excited about remote work. However,

- 50% struggle to be productive due to distractions

- 46.7% blame the loneliness of WFH for their increased stress or depression

- 37% complain about a work-life imbalance

40% of employers feel that remote work may hinder employee growth and foster loneliness and distrust in management. Similarly, 46.5% of Millennial employees feel that remote work will reduce their growth opportunities:

- 28% are concerned about their work outcomes

- 27% fear that their work performance cannot be fairly evaluated in a remote environment

- 24% fear their non-remote working peers have a clear advantage

- only 11% feel that working remotely does not match their work demands

A recent survey in April 2021 by the Japan Productivity Centre highlighted that the WFH arrangements are not ideal just yet:

- 38% complain about their physical environment

- 42% complain about Internet access

- 30% sharing data online

- 25% usability of IT tools for online meetings.

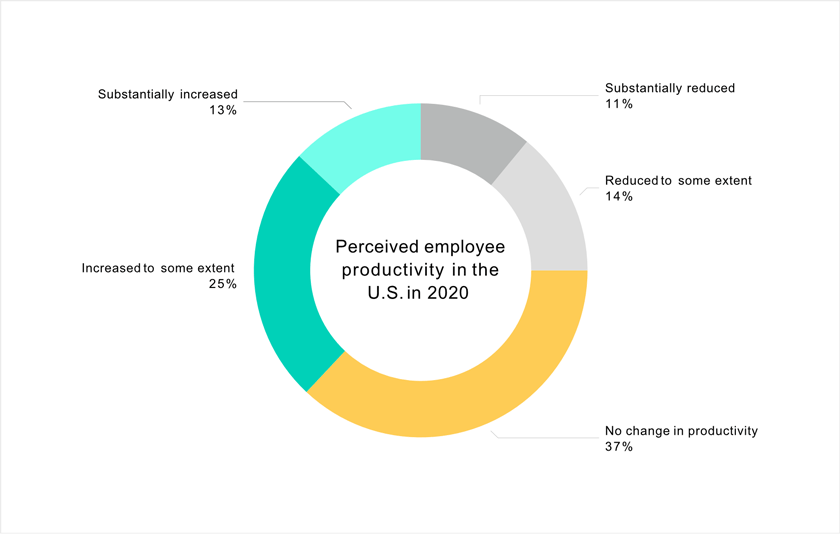

20. The United States and European countries like Germany, Sweden, the UK, and Italy perceived no loss in productivity (NRI, 2021).

There’s consensus that for Western work cultures accustomed to remote work before the pandemic, the majority of workers felt that their productivity had either remained the same or increased — 75% of American respondents, 74% in Germany, 72% in Sweden, 71% in Italy, and 60% in the UK.

Figure 3. Perceived employee productivity among American respondents in 2020.

Nevertheless, the US and the UK had the highest rates of isolation, stress, and anxiety about job loss. Respondents from the US had the most conflicting perceptions of WFH (Owl Labs, 2020):

- If in 2019 68% were not concerned that WFH would impact their career advancement, that number dropped to 57% in 2020.

- If in 2019 only 23% feared remote work would affect their careers, the percentage rose to 43%.

- Despite negative outlooks and difficult circumstances, 77% agree that WFH makes them happier.

- After COVID-19, 80% expect to work from home at least three days a week.

- 50% of employees would quit if WFH were no longer an option.

21. 90% of Australians found working from home considerably more productive (UNSW Canberra, 2020).

Australia experienced an excellent adoption rate from 2% in 2019 to 32% in 2020, discarding their previous skepticism about WFH to embracing it:

- ⅔ respondents felt they got more work done at home than in the office

- ⅓ thought they were able to undertake more complex work

- ⅓ felt they had more autonomy over when they did their work

- ⅓ worked longer hours

- ⅘ of respondents welcomed more time for themselves and their families

- ½ had more time for household chores

A 2020-study by Oracle highlights that 35% of remote workers worldwide report putting in more hours – 10 hours/week on average. This means an extra workday every week.

The top three countries working the longest hours are the United States, UAE, and India, where employees work 15+ more hours every week.

In the US, 1 in 5 respondents reported working at least 3 hours extra every day, while in the UK, it’s around 2 hours a day.

In Australia, 1 in 3 respondents reported working longer hours (UNSW Canberra, 2020):

- ½ of the responders blamed the increased workload

- ⅓ had more time due to no commuting time

- ⅓ of remote workers lost track of time

Some respondents worked longer hours because of blurred boundaries between work and home. A few respondents worked extra hours for a higher household income.

Other respondents had to increase their hours to compensate for the lost productivity. They felt guilty about not being productive enough, fearing their manager would reprimand them — 5% believed they were expected to do more work outside their usual hours.

This perceived loss in productivity is highly subjective. Managers were asked how their teams performed in the WFH environment amid the pandemic. The findings – only 8.4% were actually less productive.

Managers worldwide (70%) believed that performance was the same or even better when working from home, according to Global Workplace Analytics (2020).

How do employees feel about having their activity monitored for productivity when working remotely? In the US, 22% of respondents would be OK with it, 36% would be OK if the same method were applied to non-remote employees, 32% would be unhappy about it, and 11% would quit (Owl Labs, 2020).

In East Asian countries (i.e., Japan, China, and South Korea), around 1 in 3 employees feel like the lack of supervision makes them feel slack when working from home (NRI, 2020). To a lesser extent, this perception is found among Italian respondents (30%), Sweden (20%), the UK (12%), and Germany (10%).

One interesting finding concerning Japanese employees is that although they feel slacker when working from home, they feel more relaxed and happy about not being monitored by their superiors or colleagues. This positive outlook is what helps tackle mental fatigue and high cognitive load in challenging work environments.

Last thoughts

Remote work is here to stay. So it’s better to start learning the ropes of working remotely—the tools to use, tips to follow, and systems to employ.

Although we cannot have the exact expectations for adopting remote work in emerging countries, governments worldwide are making great strides toward better policies and companies towards building the proper infrastructure for efficient remote work.

In the context of the pandemic, working remotely has been perceived as a saving solution meant to resurrect the global economy and mitigate the spread of the virus. The reality is that the black swan of 2020 only accelerated the adoption of a work model that boasts various benefits, from positive environmental impact to greater work autonomy.

The trend has been upward in the past decade. A forecast highlights that 51% of all knowledge workers worldwide will have been working remotely by the end of 2021—we’re not there yet and it’s 2022.

First published on October 8, 2021.

Alexandra Martin

Author

Drawing from a background in cognitive linguistics and armed with 10+ years of content writing experience, Alexandra Martin combines her expertise with a newfound interest in productivity and project management. In her spare time, she dabbles in all things creative.